State of Research

The NIH Awards Allele with Grant for the Development of a New Antibody Therapy for Treating Alzheimer’s Disease

SAN DIEGO–(BUSINESS WIRE)–

The National Institute on Aging of the NIH has awarded a grant to Allele Biotechnology and Pharmaceuticals (“Allele”) to develop a new antibody therapy for treating Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, but there are currently no treatments to stop or reverse its progression.

Alongside academic collaborators, scientists at Allele have revealed a strong correlation between a previously uncharacterized target gene and Alzheimer’s disease. They discovered that expression of the gene reduces beta-amyloid production and tau phosphorylation, two components of plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, high levels of this protein in the brain can counteract loss of synapses and cognitive impairments in mice.

Allele will generate a panel of antibodies that recognize this protein with the goal of employing one of these antibodies as a therapeutic drug candidate. The antibodies’ unique size and shape allow them to pass the blood-brain barrier to reach crucial regions of the brain, and each antibody can be easily modified and engineered to heighten its therapeutic potential. Researchers at Allele hope that an antibody treatment will improve the function of its target protein in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients and ultimately reduce pathogenesis of the disease.

Recombinant antibodies represent one of the most important classes of biological therapeutics: 80% of the best selling drugs on the market are antibodies; immune checkpoint therapies and CAR-T cell therapies rely on antibodies. Continuously seeking unique antibodies against high value targets is a key focus of Allele, along with its induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) programs and iPSC-based drug screening projects. With the support of the new NIH grant, Allele will not only move closer to finding antibody drug candidates in fighting one of the most devastating diseases, but also generate long-needed research tools for other scientists to further study Alzheimer’s disease. For example, fusion of these antibodies to fluorescent proteins such as mNeonGreen can be used to image Alzheimer’s disease-related factors in cultured neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or “minibrain”-like organoids derived from human iPSCs.

View source version on businesswire.com.

Stem Cell Therapies: What’s Approved, What Isn’t, and Why Not?

With acceptance of stem cell therapies growing, so have controversies surrounding regulations.

Desperate to heal sports injuries, top professional athletes have been known to pay tens of thousands of dollars for experimental stem cell treatments that many used to find controversial. But now, stem cell therapies have become more mainstream and are no longer limited to professional athletes. Stem cell clinics offer both medical and non-medical treatments with claims of improving aesthetics and quality of life.

One recent study found over 400 websites – with the largest portion in the United States – advertising stem cell-based therapies (1); another found over 570 U.S. clinics offering stem cell interventions (2), giving more evidence that the market for stem cell therapies in the U.S. is growing at an accelerated rate. Yet these therapies are too often based on unfounded claims and lack proper clinical trials or authorized regulation. Despite what some clinics claim, very few stem cell treatments are currently available that are actually approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Hematopoietic stem cells harvested from bone marrow are routinely used in transplant procedures to treat patients with cancer or other blood or immune system disorders. Banking of umbilical cord blood is FDA-regulated and its use is approved for certain indications. Otherwise, consumers should be wary of claims by stem cell clinics implying FDA-approval.

So why aren’t more FDA-approved stem cell therapies available?

The FDA has strict regulations on using stem cell products in humans. In most cases, stem cell-based products are categorized the same way as pharmaceutical drugs. Therefore, each new therapy must go through a rigorous process including pre-clinical animal trials, phased clinical studies, and pre-market review by the FDA prior to offering the treatment in the clinic.

And with stringent regulatory requirements comes prohibitive costs. Research animals, Phase I-III clinical trials, and the regulatory demands for good manufacturing practice (GMP) labs result in an extraordinarily costly process that may hinder the progress of new therapies. The cost of developing a new drug has even been estimated to reach billions of dollars.

Nevertheless, a complete lack of regulation of stem cell therapies – as is seen in many of the stem cell clinics springing up worldwide – is clearly problematic. Alarmingly, many clinics advertise claims related to medical diseases for which there is no scientific consensus that supports their safety or efficacy. Premature commercialization of unproven therapies not only puts patients at risk, but also jeopardizes the credibility of still-developing stem cell products.

One of the most exciting outlooks for stem cell therapy is the prospect of using one’s own stem cells for personalized medicine. Should the development of an autologous stem cell product really be regulated the same way as a pharmaceutical drug, which is aimed at treating huge populations of people? If not, how should stem cell products be regulated?

In an effort to make the transition of novel stem cell products to the clinic more seamless, some countries have made significant changes in regulations. For instance, in 2014, Japan broke out a separate regulatory system for stem cell products that softened legislation dramatically to require only limited safety and efficacy data. Some argue that countries with softer regulations and less stringent safety and efficacy milestones, such as Japan, have poised themselves to become the likely pioneers in the field of regenerative medicine.

Regulatory frameworks for the clinical application of stem cell products are still evolving in most countries, including the U.S. In March, the Reliable and Effective Growth for Regenerative health Options that improve Wellness (REGROW) Act was introduced to congress. This change in legislation would remove some of the regulatory hurdles that hinder the progress of biologic therapies.

Regardless, the FDA needs to establish a more reasonable regulatory system that can evaluate the safety and efficacy of stem cell products in a more efficient manner.

1. Berger, I., et al., Global Distribution of Businesses Marketing Stem Cell-Based Interventions. Cell Stem Cell, 2016. 19(2): p. 158-62.

2. Turner, L. and P. Knoepfler, Selling Stem Cells in the USA: Assessing the Direct-to-Consumer Industry. Cell Stem Cell, 2016. 19(2): p. 154-7.

CRISPR: Growing in Popularity, But Problems Remain

The CRISPR gene-editing technology is taking the scientific world by storm, but researchers are still uncovering the platform’s potential and pitfalls.

The “Democratization” of Gene Editing

The idea of modifying human genomes using homology directed repair (HDR) has been around for decades. HDR is a widely-used repair mechanism to fix double-strand breaks in the cell’s DNA. By supplying an exogenous, homologous piece of DNA to the cell and increasing the probability of HDR occurring, changes in the DNA sequence can be introduced to the targeted area.

Some of the first gene editing platforms taking advantage of HDR used engineered endonucleases such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator like effector nucleases (TALENs). Both ZFNs and TALENs required a custom protein to target a specific DNA sequence, making them pricey and very difficult to engineer. The more recently developed CRISPR/Cas9 platform works differently: instead of using a protein, the Cas enzyme uses a small guide RNA to locate the targeted DNA, which is then cut. CRISPR is more low tech and “user-friendly” than other platforms, as users are no longer required to do the onerous chore of protein engineering. Now, the ability to modify genomes can be done without extensive training or expensive equipment. CRISPR can be used for knocking out genes, creating reporter or selection genes, or modifying disease-specific mutations—by practically anyone with basic knowledge of molecular biology.

The CRISPR Revolution

Because of its relative simplicity and accessibility, it is no wonder that life scientists from all over the world are eager to incorporate CRISPR into their research. One of the most remarkable things about CRISPR technology is how quickly its popularity has allowed the platform to evolve. The discovery revealing that CRISPR can be used for RNA-programmable genome editing was first published in 2012 (1). Since then, about 2,000 manuscripts have been published including this technology and millions of dollars have been invested into CRISPR-related research and start-up companies. Scientists have developed a myriad of applications for CRISPR, which can be used in practically any organism under the sun. The popularity and progress of gene editing promises revolutionary advancements in virtually every scientific field: from eradicating disease-carrying mosquitoes to creating hypoallergenic eggs and even curing genetic diseases in humans.

There is no doubt that CRISPR has enormous potential – the widespread interest and rapid progress are evidence of that. The main reason CRISPR has been so widely adapted is because development and customization is way less labor-intensive and time-consuming than previous methods. But material preparation is a miniscule part of the CRISPR platform. Contrary to popular belief, just because CRISPR is easier to use than other methods of gene editing, it is not “easy.”

Hitting the Bull’s-Eye

To understand the limitations of this gene editing technology, it’s important to understand more about how CRISPR works. The CRISPR/Cas9 system functions by inducing double-strand breaks at a specific target and allowing the host DNA repair system to fix the site of interest. Cells have two major repair pathways to fix these types of breaks, Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and homology directed repair (HDR). NHEJ is faster and more active than HDR and does not require a repair template, so NHEJ is the principle means by which CRISPR/Cas9-induced breaks are repaired. If the editing goal is to induce insertions or deletions through NHEJ to cut out a part of a gene, then using the CRISPR platform is less complicated. But directing CRISPR to correct a gene with exogenous DNA does not work very well, as the rate of HDR occurring at the site of interest is often very low, sometimes less than 1%. For precise genome-editing through CRISPR, it is essential to have HDR while minimizing damaging NHEJ events.

Increasing the rate of HDR is not trivial. Recent research has shown that the conditions for the two repair pathways vary based on the cell type, location of the gene, and the nuclease used (2). Besides, optimizing CRISPR to better control HDR versus NHEJ events is only half the battle. One of the greatest challenges in using CRISPR is to be able to quickly and accurately detect different genome-editing events. Many scientists measure changes by sequencing. A more sophisticated method is to use droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) (3), but many labs have limited accessibility to ddPCR systems. After screening multiple clones and detecting the desired genetic edit comes what is usually the most laborious and time-consuming step: pure clonal isolation. Because each individual cell is affected by CRISPR independently, isogenic cell lines must be established.

Improving CRISPR

CRISPR has become the gold standard for many scientists now that the potential to perform gene editing has become so universal. Top journals expect isogenic lines for characterizing genes and mutations, and many researchers feel pressured to include such experiments to stay competitive in grant proposals. Moreover, a federal biosafety committee has recently approved the first study in patients using this genome-editing technology. To keep up with the pace of this rapidly moving field, significant improvements in CRISPR technology need to be made.

First, a better grasp of the basic principles behind CRISPR is likely to lead to improvements in targeting and efficiency. For example, understanding how the cell type, locus, and genomic landscape affect the targeting and cutting of Cas9 could lead to higher efficiencies of HDR. Similarly, engineering Cas9 and the guide RNA to maximize on-target activity could also accelerate the technology’s success. Screening the ability of the guide RNA to target the intended sequence can be performed in vitro by assessing the Cas9-mediated cuts on a PCR-amplified fragment of DNA; this method often gives a good indication of what to expect in cells. Another hindrance to CRISPR technology is that currently, all methods to detect genome changes require destruction of the cells of interest. Development of an assay to detect chromosomal changes in live cells – reminiscent of live-cell RNA detection – would immensely improve the processes of clonal screening and isolation.

Besides the technical challenges that come with maximizing on-target edits is that Cas9 frequently has off-target effects, producing insertions or deletions at unintended sites. Online algorithms can predict where some of these cuts are likely to occur, but currently, there is no efficient method to identify all possible off-target sites (4). To complicate things further, no two human genomes are identical. Due to genetic variation, predicting off-target effects based on reference genomes remains a challenge. Because so much of the hype around CRISPR surrounds the potential to treat human diseases, it is imperative to make sure that CRISPR does not introduce detrimental changes elsewhere in the genome before therapeutic use in humans. Standard screening methods and biological assays need to be established to robustly assess potential damage done to other sites in the genome and to measure its impact on cell function and mutagenesis.

Despite its shortcomings, the hub of activity surrounding CRISPR has been astounding. And with the force of thousands of scientists working on this technology, the possibilities for the future of CRISPR are boundless.

References

- Jinek, M., et al., A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science, 2012. 337(6096): p. 816-21.

- Miyaoka, Y., et al., Systematic quantification of HDR and NHEJ reveals effects of locus, nuclease, and cell type on genome-editing. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 23549.

- Hindson, B.J., et al., High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem, 2011. 83(22): p. 8604-10.

- Stella, S. and G. Montoya, The genome editing revolution: A CRISPR-Cas TALE off-target story. Bioessays, 2016. 38 Suppl 1: p. S4-s13.

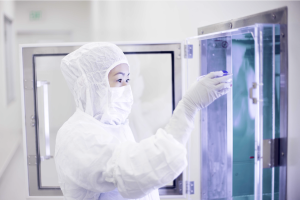

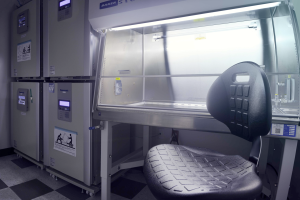

Generation of Human Stem Cells under Good Manufacturing Practice: Facility Update

Last year Allele dedicated a new building space for cleanroom operations to provide a cell banking service for personalized medicine. This facility will be the center of current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) production of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using Allele’s proprietary synthetic mRNA platform. Over the past three months, progress to get the facility up and running has been substantial. Our facility includes four main modules: the reception area and doctors’ offices, a Fibroblast Isolation and Maintenance room, a Reprogramming and iPSC Maintenance room, and a Quality Control room. Air handling, which is a major component of the environmental control system, has been installed and validated. Equipment such as biosafety cabinets, incubators, and refrigerators have been installed and qualified, as well as equipment for performing essential quality control steps. To standardize personnel-related steps of cGMP processing, we have prepared rigorous SOPs and have extensively trained individual manufacturing operators. Overall, we are enthusiastic about the facility’s progress and are committed to delivering the best possible service as the industry leader in iPSC banking.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

cGMP Compliance: What Does It Mean for Your Cell Lines?

As the promise for cell-based therapy grows, the interest in making clinically relevant cell lines has skyrocketed for industrial and academic researchers alike. For translation into human therapies, cell-based products must be made following current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP). Many groups have already claimed to generate cell lines that are “cGMP-compliant,” “cGMP-ready,” or “certifiable under cGMP.” But what does it take to be truly cGMP-compliant, and what practices can you introduce in your lab to comply with cGMP standards?

A common misconception in the United States is that a facility is granted a ‘cGMP license’ from the government to manufacture cGMP-grade products. Rather, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) evaluates the manufacturing process for each product to determine if it is compliant with cGMP standards. The primary concern when it comes to deriving cell-based products for therapies is making sure that the product is derived in a safe and reproducible manner. To ensure maximum quality assurance, researchers should

• choose reliable, xenogeneic-free raw materials,

• establish and monitor a clean environment,

• qualify all equipment and software,

• remove variation in laboratory procedures by creating detailed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and by providing rigid process validation at each step.

Nevertheless, even establishing robust quality assurance does not imply that the process is scalable for commercial production. In the world of biologics, “the product is the process.” A requisite step to ensure a smooth transition to cGMP practice is to ensure that the process of manufacturing is not altered due to changes in production scale. For example, depending on the therapy, millions or billions of cells may be required for a single patient. Therefore, it is in the best interest of the researchers to develop a scalable method at the beginning to avoid revamping the entire process (e.g., changing from adherent cells to suspension). Along these lines, the quality control (QC) requirements of cell-based products should be carefully considered and not have to include difficult-to-assay tests. For example, some cell lines have been qualified as cGMP-compliant upon conversion from research-grade conditions to cGMP quality standards. Rigorous tests were performed on the converted lines to ensure that the cells were free of contamination. Even though strict measures were carried out to ensure cGMP compliancy, deriving cell lines in this manner makes scalability and reproducibility a challenge. Ideally, the entire process of deriving cell products for clinical use should be performed under cGMP conditions: from the acquisition of human tissue to the manufacturing, testing, and storage of derivative cell products.

Another important consideration when instituting cGMP-compliance is documentation. Each process must be described with rigorous SOPs, the training of individual manufacturing operators must be well-documented, and the entire established process must be validated and well noted. Failure to document—in the eyes of the FDA—is often equated with failure to perform the underlying activity. It is equally important to remain ‘current.’ The FDA expects manufacturing processes to stay up-to-date with current regulations, even as policies change.

For an academic lab, closely aligning with cGMP standards can ensure that the resulting cell lines are comparable to other truly cGMP-produced products used during clinical trials. It is in the best interest of academic researchers to establish rigorous SOPs and use qualified reagents and equipment, even if it is not possible to carry out all steps in a certified cleanroom. Whenever possible, it is advisable to acquire truly cGMP cell lines from appropriate sources for preclinical projects; if prohibited by costs or other reasons, it is recommended to use a protocol that is as close to cGMP as possible.

Categories

- Allele Mail Bag

- cGMP

- Customer Feedback

- Fluorescent proteins

- iPSCs and other stem cells

- nAb: Camelid Antibodies, Nanobodies, VHH

- Next Generation Sequencing (NextGen Seq)

- NIH Budget and You

- oligos and cloning

- Open Forum

- RNAi patent landscape

- SBIR and Business issues

- State of Research

- Synthetic biology

- Uncategorized

- Viruses and cells

- You have the power

Archives

- October 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- January 2018

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- February 2016

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- June 2015

- March 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008