Open Forum

Roundtable on cGMP Stem Cell Manufacturing

Allele Biotechnology & Pharmaceuticals is hosting a cGMP Stem Cell Manufacturing Roundtable to discuss ways to accelerate stem cell-based therapies toward clinical development and commercialization. The roundtable will bring together top minds from academic settings, cGMP facilities, and biotech industries in an informal setting to explore partnerships and avenues for developing effective and marketable iPSC-derived therapies.

The meeting will be held on April 20th at The Hilton on Torrey Pines and will consist of four sessions covering (1) existing cGMP facilities, (2) manufacturing and quality systems, (3) regulatory concerns, and (4) business strategy.

Meeting highlights will be produced to summarize the presentations and discussions. For inquiries, contact info@allelebiotech.com or call 858-587-6645.

Nanoantibody Development Shows Momentum —Join the Dance Now Or Play Catch-up Forever

Oct 8, 2017, San Diego, CA: Last week, Belgian company Ablynx Inc. announced IPO plans based on robust results from a Phase III study with caplacizumab, the very first nanoantibody drug ready for market.

Caplacizumab targets von Willebrand factor (vWF), will benefit patients afflicted with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), a life-threatening autoimmune blood clotting disorder.

The Phase III study (named as HERCULES) met the primary endpoint, namely a statistically significant reduction in time to platelet count response in patients, besides providing standard-of-care. Patients on caplacizumab were 1.5 times more likely to achieve platelet count response at any given time point, compared to placebo control. In addition, the study also met two key secondary endpoints, namely, a 74% reduction in the percentage of patients with recurrence of aTTP or related death, and absence of any major thromboembolic event during study. In addition, the proportion of patients with a recurrence of aTTP during the study period (including the 28 day follow-up period after discontinuation of the drug) was 67% lower in the caplacizumab arm compared to the placebo arm, demonstrating the sustained benefits from the treatment.

Ablynx immediately sought to capitalize the outstanding clinical benefits provided by caplacizumab. On the same day of publicizing their clinical trial results, Ablynx announced filing of a Registration Statement on Form F-1 with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for a proposed stock offering (IPO in the US in the form of American Depositary Shares (“ADSs”) and private placement of ordinary shares in Europe). Ablynx plans to obtain $150 million to finance its commercialization of their new nanoantibody in the U.S. and Europe. With the new developments, the company also expects to accelerate the clinical development of other nanoantibodies, including ALX-0171 which targets respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection.

With these exciting news out on the market, now is a great time for the traditional players in the pharmaceutical industry to take a good look and seriously evaluate the possibility to add nanoantibody to their development portfolio. The time is now because success of the new Ablynx drug has minimized the investment risk by proving the feasibility, potential, and advantages of nanoantibodies. The time is now because the field of therapeutic nanoantibodies is still wide open, unlike other crowded, highly competitive arena of conventional antibodies. The time is now, also because with nanoantibodies just starting to get onto the map, an investment in nanoantibodies has the potential of delivering extraordinary returns.

Allele is actively involved in the preclinical development of therapeutic nanoantibody for the past several years, and has accumulated significant IP and technological know-how in this space, and a dozen or so programs ranging from oncology to inflammation. We have a high-speed new technology by which we can get dozens of new nanoantibodies per year, and a pipeline by which we routinely perform humanization, bi- or multi-valency, and expression optimization. We welcome inquiries into our development program, collaboration or joint development proposals, and in exploring investment opportunities with us.

Contact Alleleblog or the Allele nAb team: Dr. Jenny Higginbotham, jhigginbotham@allelebiotech.com; Dr. Nobuki Nakanishi, nnakanishi@allelebiotech.com

CRISPR: Growing in Popularity, But Problems Remain

The CRISPR gene-editing technology is taking the scientific world by storm, but researchers are still uncovering the platform’s potential and pitfalls.

The “Democratization” of Gene Editing

The idea of modifying human genomes using homology directed repair (HDR) has been around for decades. HDR is a widely-used repair mechanism to fix double-strand breaks in the cell’s DNA. By supplying an exogenous, homologous piece of DNA to the cell and increasing the probability of HDR occurring, changes in the DNA sequence can be introduced to the targeted area.

Some of the first gene editing platforms taking advantage of HDR used engineered endonucleases such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator like effector nucleases (TALENs). Both ZFNs and TALENs required a custom protein to target a specific DNA sequence, making them pricey and very difficult to engineer. The more recently developed CRISPR/Cas9 platform works differently: instead of using a protein, the Cas enzyme uses a small guide RNA to locate the targeted DNA, which is then cut. CRISPR is more low tech and “user-friendly” than other platforms, as users are no longer required to do the onerous chore of protein engineering. Now, the ability to modify genomes can be done without extensive training or expensive equipment. CRISPR can be used for knocking out genes, creating reporter or selection genes, or modifying disease-specific mutations—by practically anyone with basic knowledge of molecular biology.

The CRISPR Revolution

Because of its relative simplicity and accessibility, it is no wonder that life scientists from all over the world are eager to incorporate CRISPR into their research. One of the most remarkable things about CRISPR technology is how quickly its popularity has allowed the platform to evolve. The discovery revealing that CRISPR can be used for RNA-programmable genome editing was first published in 2012 (1). Since then, about 2,000 manuscripts have been published including this technology and millions of dollars have been invested into CRISPR-related research and start-up companies. Scientists have developed a myriad of applications for CRISPR, which can be used in practically any organism under the sun. The popularity and progress of gene editing promises revolutionary advancements in virtually every scientific field: from eradicating disease-carrying mosquitoes to creating hypoallergenic eggs and even curing genetic diseases in humans.

There is no doubt that CRISPR has enormous potential – the widespread interest and rapid progress are evidence of that. The main reason CRISPR has been so widely adapted is because development and customization is way less labor-intensive and time-consuming than previous methods. But material preparation is a miniscule part of the CRISPR platform. Contrary to popular belief, just because CRISPR is easier to use than other methods of gene editing, it is not “easy.”

Hitting the Bull’s-Eye

To understand the limitations of this gene editing technology, it’s important to understand more about how CRISPR works. The CRISPR/Cas9 system functions by inducing double-strand breaks at a specific target and allowing the host DNA repair system to fix the site of interest. Cells have two major repair pathways to fix these types of breaks, Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and homology directed repair (HDR). NHEJ is faster and more active than HDR and does not require a repair template, so NHEJ is the principle means by which CRISPR/Cas9-induced breaks are repaired. If the editing goal is to induce insertions or deletions through NHEJ to cut out a part of a gene, then using the CRISPR platform is less complicated. But directing CRISPR to correct a gene with exogenous DNA does not work very well, as the rate of HDR occurring at the site of interest is often very low, sometimes less than 1%. For precise genome-editing through CRISPR, it is essential to have HDR while minimizing damaging NHEJ events.

Increasing the rate of HDR is not trivial. Recent research has shown that the conditions for the two repair pathways vary based on the cell type, location of the gene, and the nuclease used (2). Besides, optimizing CRISPR to better control HDR versus NHEJ events is only half the battle. One of the greatest challenges in using CRISPR is to be able to quickly and accurately detect different genome-editing events. Many scientists measure changes by sequencing. A more sophisticated method is to use droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) (3), but many labs have limited accessibility to ddPCR systems. After screening multiple clones and detecting the desired genetic edit comes what is usually the most laborious and time-consuming step: pure clonal isolation. Because each individual cell is affected by CRISPR independently, isogenic cell lines must be established.

Improving CRISPR

CRISPR has become the gold standard for many scientists now that the potential to perform gene editing has become so universal. Top journals expect isogenic lines for characterizing genes and mutations, and many researchers feel pressured to include such experiments to stay competitive in grant proposals. Moreover, a federal biosafety committee has recently approved the first study in patients using this genome-editing technology. To keep up with the pace of this rapidly moving field, significant improvements in CRISPR technology need to be made.

First, a better grasp of the basic principles behind CRISPR is likely to lead to improvements in targeting and efficiency. For example, understanding how the cell type, locus, and genomic landscape affect the targeting and cutting of Cas9 could lead to higher efficiencies of HDR. Similarly, engineering Cas9 and the guide RNA to maximize on-target activity could also accelerate the technology’s success. Screening the ability of the guide RNA to target the intended sequence can be performed in vitro by assessing the Cas9-mediated cuts on a PCR-amplified fragment of DNA; this method often gives a good indication of what to expect in cells. Another hindrance to CRISPR technology is that currently, all methods to detect genome changes require destruction of the cells of interest. Development of an assay to detect chromosomal changes in live cells – reminiscent of live-cell RNA detection – would immensely improve the processes of clonal screening and isolation.

Besides the technical challenges that come with maximizing on-target edits is that Cas9 frequently has off-target effects, producing insertions or deletions at unintended sites. Online algorithms can predict where some of these cuts are likely to occur, but currently, there is no efficient method to identify all possible off-target sites (4). To complicate things further, no two human genomes are identical. Due to genetic variation, predicting off-target effects based on reference genomes remains a challenge. Because so much of the hype around CRISPR surrounds the potential to treat human diseases, it is imperative to make sure that CRISPR does not introduce detrimental changes elsewhere in the genome before therapeutic use in humans. Standard screening methods and biological assays need to be established to robustly assess potential damage done to other sites in the genome and to measure its impact on cell function and mutagenesis.

Despite its shortcomings, the hub of activity surrounding CRISPR has been astounding. And with the force of thousands of scientists working on this technology, the possibilities for the future of CRISPR are boundless.

References

- Jinek, M., et al., A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science, 2012. 337(6096): p. 816-21.

- Miyaoka, Y., et al., Systematic quantification of HDR and NHEJ reveals effects of locus, nuclease, and cell type on genome-editing. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 23549.

- Hindson, B.J., et al., High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem, 2011. 83(22): p. 8604-10.

- Stella, S. and G. Montoya, The genome editing revolution: A CRISPR-Cas TALE off-target story. Bioessays, 2016. 38 Suppl 1: p. S4-s13.

Researchers use GFP nano antibody to study organ growth

Single-domain nano antibodies have a broad range of applications in biochemistry due to their small size, high affinity, and high specificity. Now, a team of researchers from the University of Basel and the University of Zurich has demonstrated that nano antibodies can be used for research in complex living organisms such as Drosophila, uncovering another new and exciting application for nano antibodies.

The team used nano antibodies to develop an assay for studying morphogens, molecules that regulate the pattern of tissue growth and the positions of various cell types within tissue. Morphogens form long-range concentration gradients from a localized source, ultimately determining the fate and arrangement of cells that respond to that gradient. Drosophila is a classic model system for understanding how morphogens regulate organ development. One morphogen called Dpp controls uniform proliferation and growth of the wing imaginal disc. Yet because Dpp is an extracellular, diffusible protein, it is difficult to immobilize in situ. Therefore, despite over 20 years of studying the role of Dpp as a morphogen, the lack of a dynamic system for controlling Dpp gradients has prevented researchers from understanding precisely how Dpp governs development of the wing disc.

By developing a novel synthetic system using nano antibodies, the researchers were able to modulate the concentration gradient of Dpp at the protein level. Their system—coined “morphotrap”—uses a membrane-bound GFP nano antibody to “trap” GFP-tagged Dpp at different locations along the wing imaginal disc. By tethering Dpp in a controlled spatial manner, researchers were able to determine how Dpp gradients affect wing disc development. They discovered that the gradient of Dpp is required for the patterning of the wing disc but not for lateral growth, disproving one of the field’s popular theories that address the role of Dpp. In addition to resolving the controversy with respect to the role of Dpp as a morphogen, this study pioneers a new method for using nano antibodies in situ.

“Dpp spreading is required for medial but not for lateral wing disc growth.”

Harmansa S., Hamaratoglu F., Affolter M., Caussinus E.

Nature. 2015 Nov 19;527(7578):317-22. doi: 10.1038/nature15712. Epub 2015 Nov 9.

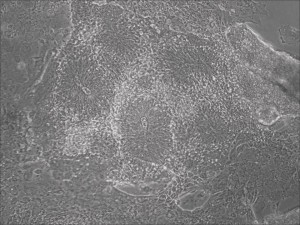

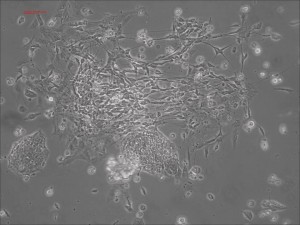

Picture Blog: A Short Path from Human mRNA-iPSCs to Neurons in Record Speed

Traditional differentiation protocols use embryoid body (EB) formation as the first step of lineage restriction to mimic early human embryogenesis, which is then followed by manual selection of neuroepithelial precursors. This procedure is tedious and often inconsistent. We have developed a novel neural differentiation scheme that directs human iPSCs (created with the Allele 6F mRNA reprogramming kit) that progressed, as attached culture, to neural precursor cells (NPCs) in just 4-6 days, half the time it typically takes by other methods. From NPCs it takes about another 5-6 days for neural rosettes to form (see figures below); upon passage, cells in neural rosettes differentiate into neurons in 24 hours.

The neural progenitors at the rosettes stage can be stocked and expanded, before differentiated into different types of neurons. We are working on specifically and efficiently different these neural progenitor cells into dopaminergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic, and other types of sub-types of neurons with Allele’s technologies (Questions? email the Allele Stem Cell Group at iPSatAllelebiotech.com).

Neural rosettes formed efficiently in wells without going through EB.

Human iPSC-derived neurons are created in a short regimen developed at Allele Biotech

Categories

- Allele Mail Bag

- cGMP

- Customer Feedback

- Fluorescent proteins

- iPSCs and other stem cells

- nAb: Camelid Antibodies, Nanobodies, VHH

- Next Generation Sequencing (NextGen Seq)

- NIH Budget and You

- oligos and cloning

- Open Forum

- RNAi patent landscape

- SBIR and Business issues

- State of Research

- Synthetic biology

- Uncategorized

- Viruses and cells

- You have the power

Archives

- October 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- January 2018

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- February 2016

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- June 2015

- March 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008