Picture Blog: mRNA Reprogramming for Human iPSCs without B18R!

Human induced pluripotent stem cells provide a great route towards personalized medicine and high accuracy drug screening. Allele Biotech has developed the most efficient method of making human iPSCs by using enhanced mRNAs, which have been adopted by leading pharmaceutical companies for clinical trials. The effects from medium-supplementing mRNAs are robust yet transient, and highly specific compared to both miRNAs (off-targets) and small molecules (unknown targets). To repress cellular immune response to introduced RNA molecules, viral protein B18R was previously used during mRNA reprogramming.

B18R is relatively expensive and inconvenient to use because it requires pre-aliquoting and -80C storage. The protocol has recently been dramatically improved at Allele through an NIDA-funded project. In our latest reprogramming run, all we needed to do was to include mRNA complex in the supplement during medium change for just a week without the need of adding any other type of molecules (such as B18R, miRNA, or chemicals) to help the mRNA mix, unlike all other known mRNA-reprogramming protocols. This advancement can make reprogramming human fibroblasts to footprint-free and xeno-free iPSCs a routine experiment for any lab to perform.

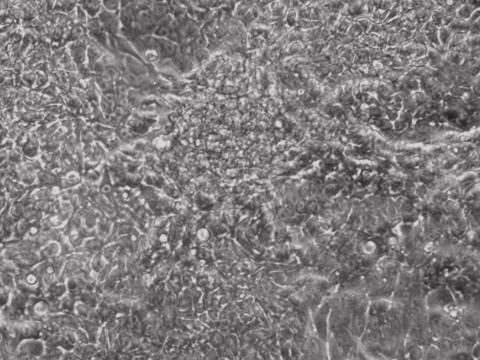

Human R-iPSCs were created without the need of B18R, dramatically reduced the cost and inconvenience. Shown is a newly formed iPSC colony.

Picture Blog: More Efficient Reprogramming for Creating Induced Stem Cells (iPSCs)

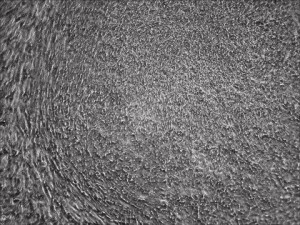

Researchers at Allele Biotech achieved reprogramming of human fibroblasts into iPSCs within one week by including mRNA transfection supplement in daily medium change, at “bulk conversion” efficiency, and with cells seeded at a much wider density range compared to our previous publications. These significant improvements will further facilitate high throughput, large scale iPSC production using Allele’s feeder-free, xeno-free, footprint-free reprogramming, which was already a preferred method for both clinical applications and stem cell banking. The reprogramming project is currently being funded by the NIDA/NIH.

Visualizing Endogenous Synaptic Proteins in Living Neurons

The recently published method is based on the generation of disulfide-free “intrabodies”, a structure from the 10th fibronectin type III domain known as FingRs. These affinity molecules were fused to GFP for direct fluorescence miscroscopy. The FingRs do not need di-sulfite bonds and are therefore better folders in mammalian cells. Specifically, a library was screened with in vitro display to identify FingRs that bind two synaptic proteins, Gephyrin and PSD95. After the initial selection, the researchers from USC secondarily screened binders using a cellular localization assay to identify potential FingRs that bind at high affinity in an intracellular environment. As it turned out, only 10-20% of the original positive clones bind well inside the cells, suggesting this type of further screening was a critical step.

The expression of intrabody is transcriptionally regulated by the target protein through a ZFN-repressor fusion. This transcriptional control system matches the expression of the intrabody to that of the target protein regardless of the target’s expression level. This design virtually eliminates unbound FingR, resulting in very low background that allows unobstructed visualization of the target proteins. As result, the FingRs presented in this study enabled live cell visualization of excitatory and inhibitory synapses, and apparently without affecting neuronal function.

Technically, the reason to use in vitro mRNA display was required by the need to use a large library (>10exp12, beyond the limit of the more commonly used phase display) to find good binders. A similar visualization system can be established using more potent affinity domains such as the VHH single-domain antibodies that have only one, sometimes dispensable, di-sulfite bond. The VHH domain nanobodies can be more easily isolated from camelid animals. Another improvement to the visualization system can be made by using stronger, superresolution-ready FPs such as mNeonGreen or mMaple to enable single molecule imaging, which is particularly interesting for studying synapses and applied to the BRAIN initiative.

Gross et al. Neuron, June 2013, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23791193

Genome Modification—a Practical Approach

The ability to modify genomes has always been fervidly sought after by molecular, developmental biologists and geneticists as it would provide them with the means for finding out what a particular piece of the genome may do in the biological process they are studying. The discovery of naturally existing P-element helped a generation of Drosophila geneticists and made the fruit fly a prime model system for gene function studies in the 80’s and 90’s. But P-elements inserted at uncontrolled sites, making it essentially a gene transfer vehicle without much control. The introduction of prokaryotic recombination systems, e.g. LoxP and Cre, provided researchers with tools to obtain more control of the inserted genes in a host chromosome during a biological process such as development. Transposons like Sleeping Beauty, Piggybac, or Tol2 made similar experiments possible in mammalian cells.

Still, the randomness of transposon-type elements’ insertion, much like retrovirus or lentivirus, could cause trouble if they land in an undesirable spot. Methods of inserting transgenes only in well-known, harmless, and transcriptionally active regions, so called “safe harbors”, were subjects of interest of researchers and NIH grant topics in the past couple of years under “directed genome editing”. Gene knock-out or knock-in can be achieved through vector-mediated homologous recombination such as the rAAV genome engineering system and the “TARGATT” system, which are commercially available as kits or services.

However, instead of inserting an exogenous gene, it is often highly desirable to modify an endogenous genome sequence, which requires the modification apparatus to first recognize the target sequence. ZFN and TALEN both recognize DNA targets through specific nucleotide binding protein domains, with TALEN having more flexibility if assembled in a “Lego”-like format because each domain can specifically recognize a “C”, “G”, “T”, or “A” base. The description of using CRISPR/cas system in a recent burst of publications opened up new ways of binding to specific DNA sequences and nicking or severing the dsDNA. This system does not require engineeredDNA binding domain assembly; instead, it uses a guide RNA to find the target DNA sequence to direct endonuclease, in a sense quite like RNAi. However, the enthusiasm about CRISPR/cas was somewhat dampened by a report last month in Nature Biotechnology that reported off-target effects of CRISPR/cas was much higher than ZFN and TALEN. Particularly, if mismatches are located in the 5’ portion of the guide RNA targeting sequence, they can be well tolerated up to 3 or 4, even 5 mismatches. Unfortunately this is also similar to the tolerance of the RNAi matching region outside the core 12-base region. The difference is: for RNAi, the off-target damage is temporary and ignorable if the extent is insignificant compared to the effects on the intended target while for CRISPR/cas, an off-target cut on the chromosome is permanent.

On the positive side, in an even more recent publication in Nature Methods, mutant strains of C. elegans were obtained using the CRISPR/cas system and no evidence was found for off-target changes, at least not in an overwhelming fashion. Much value of the estimates of off-target effects relates to the methods used for analysis. Currently, most of the studies looked at potential off-target sides by searching for partial matches. In the future, whole genome sequencing will be increasingly required for submitting such publications.

On a practical note, if you intend to take a dive and try to use any one of these methods, your number one problem will be that none of the methods will result in 100% modification even if you can ignore the off-target problems for now. Therefore, many of our customers ask about a screening strategy. One could use traditional drug selection and fluorescent protein (FP)-based sorting, but these can only help you find cells that are successfully transfected with the ZFN, TALEN, or CRISPR/cas expressing DNA molecules, not necessarily having the genome modification result. We have formulated the idea of inserting the target site into an FP-bearing plasmid as a surrogate target cutting indicator, and use another FP to track transfection of the TALEN plasmid. Nonetheless, in the end, PCR-amplifying the target region of the chromosome and doing either an enzymatic mismatch detection assay (e.g. T7 endonuclease) or sequencing is the only way to know for sure whether genome editing has occurred.

Allele Biotech Receives $200,000 Grant to Update Its mRNA Reprogramming Commercial Products and Services

On June 10, 2013 Allele received an SBIR award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA/NIH) entitled “Revolutionary Technology for Efficient Derivation of Human iPSCs with Messenger RNA”. The goal of the proposed project is to provide to the biomedical research market an advanced reagent kit and services for highly efficient reprogramming of high quality human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). At the core of this kit is the Allele team’s recent development transcribed messenger RNA (mRNA). Compared to other reprogramming methods, such as lentivirus, Sendai virus, protein, small molecules or any combinations of these reagents, our new generation of the mRNA method often requires less than half the time while sometimes achieving “bulk conversion” efficiency.

While the Allele reprogramming technology was designed for clinical use as the process is feeder-free, xeno-free, chromosome integration-free, as well as without the need for cell splitting, PI, Dr. Jiwu Wang states, “Our purpose of executing the NIH-funded research it to make our method so easy that any researcher can integrate iPSC into his or her projects.” In addition to the extremely high efficiency, mRNA-generated iPSCs should also be more stable because there are no genetic alterations, more uniform among all clones as there is no clonal event, and ultimately suitable for future autologous cell therapy now that creating iPSCs from patient tissue cells should no longer be the rate-limiting steps.

Allele’s business model is to provide cGMP-grade iPSCs to pharmaceutical companies and perform large scale reprogramming by partnering first with university-affiliated hospitals. Great progress has been made in both directions, which has prompted the initiation of a cGMP unit within Allele’s newly acquired building in San Diego.

Categories

- Allele Mail Bag

- cGMP

- Customer Feedback

- Fluorescent proteins

- iPSCs and other stem cells

- nAb: Camelid Antibodies, Nanobodies, VHH

- Next Generation Sequencing (NextGen Seq)

- NIH Budget and You

- oligos and cloning

- Open Forum

- RNAi patent landscape

- SBIR and Business issues

- State of Research

- Synthetic biology

- Uncategorized

- Viruses and cells

- You have the power

Archives

- October 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- January 2018

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- February 2016

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- June 2015

- March 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008