iPSCs

Picture Blog: More Efficient Reprogramming for Creating Induced Stem Cells (iPSCs)

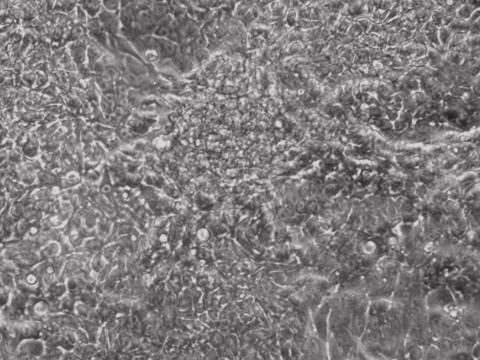

Researchers at Allele Biotech achieved reprogramming of human fibroblasts into iPSCs within one week by including mRNA transfection supplement in daily medium change, at “bulk conversion” efficiency, and with cells seeded at a much wider density range compared to our previous publications. These significant improvements will further facilitate high throughput, large scale iPSC production using Allele’s feeder-free, xeno-free, footprint-free reprogramming, which was already a preferred method for both clinical applications and stem cell banking. The reprogramming project is currently being funded by the NIDA/NIH.

Autologous versus Allogeneic iPSCs in Immune Rejection

The enthusiasm of using autologous induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for cell replacement therapy was dampened by a publication 2 years ago in Nature (Zhao et al, 2011), which suggested that even syngeneic (genetically identical) iPSCs could still invoke strong immune rejection because, as the authors in Yang Xu’s lab at UCSD explained, the iPSCs overexpress a number of tumor antigens possibly linked to genomic mistakes acquired during reprogramming. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), on the other hand, did not show similar rejection problems in the same studies, indicating that the immune responses were due to somatic reprogramming.

If proven true, the iPSC-specific immune rejection would have been the biggest hurdle for any iPSC-inspired clinical plans. Naturally, a number of labs performed series of experiments that were aimed at addressing the concerns raised by Zhao et al. This month in Cell Stem Cell, researchers from Ashleigh Boyd’s lab at Boston University demonstrated that autologous (self) or syngeneic iPSCs or their derivatives were not rejected (Guha et al. 2013). These iPSCs behaved essentially the same as ESCs in transplantation settings. When immunogenicity was measured in vitro by monitoring T cell responses in co-culture, no immune response was observed either. In contrast, cells and tissues from allogeneic (genetically different) iPSCs were rejected immediately.

In light of this new publication and an earlier Nature paper (Araki et al. 2013), Kaneko and Yamanaka have commented that autologous iPSCs still seem to have a very good chance of being used in cell replacement therapy, pending, of course, additional research and trial results. In their Preview article in Cell Stem Cell (Kaneko and Yamanaka 2013) two points were particularly emphasized: 1) autologous iPSCs are preferred because of the lack of immune rejection; 2) iPSCs generated with footprint-free reprogramming technologies are preferred because the problems reported by Zhao et al 2011 might be correlated with the use of retroviral vectors (even though they also used episomal plasmid-reprogrammed iPSCs). We strongly support both of these points and believe that they point out the direction of future stem cell therapies.

However, we do not agree with the last statement by Kaneko and Yamanaka in that article stating that as a result of the cost and time required to generate iPSC lines from each patient in GMP facilities, iPSC lines from HLA homologous donors will be the choice going forward to clinical applications. First of all, HLA-matched iPSCs should be closer to allogeneic than to autologous iPSCs. From what we just learned in the last round of debates, the field should certainly go with autologous. Second, generating foot-print free iPSCs may already not be the rate-limiting step, even in cGMP protocols, compared to downstream differentiations that are required using any pluripotent stem cells. We have shown that human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed in a completely feeder-free, xeno-free, passage-free process, using only mRNAs, in just over a week, achieving sometimes “bulk conversion”—converting nearly all cells within a well into iPSCs (Warren et al. 2012). We have drawn up a plan to establish cGMP protocols and to quickly apply autologous, footprint-free iPSCs to clinical programs through partnerships. The field can move at a faster speed, with all due scientific vigor and caution, if the best technology available is chosen for building the foundation.

Zhao, T., Z.N. Zhang, Z. Rong, and Y. Xu, Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature, 2011. 474(7350): p. 212-5.

Guha, P., et al., Lack of immune response to differentiated cells derived from syngeneic induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell, 2013. 12(4): p. 407-1

Kaneko, S. and S. Yamanaka, To Be Immunogenic, or Not to Be: That’s the iPSC Question. Cell Stem Cell, 2013. 12(4): p. 385-6.

Araki, R., et al., Negligible immunogenicity of terminally differentiated cells derived from induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cells. Nature, 2013. 494(7435): p. 100-4.

Warren, L., Y. Ni, J. Wang, and X. Guo, Feeder-free derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells with messenger RNA. Sci Rep, 2012. 2: p. 657.

Conducting Massively Parallel Sequencing

One of the major breakthroughs in modern biology is the development of massively parallel sequencing, also called next generation sequencing (NGS), which enabled the complete delineation of the human genome more than a decade ago. Since then many more species’ genomes have been sequenced, and the cost per genome has dropped from billions to mere thousands of dollars. New discoveries are being made as a result of the capability many research teams now possess to not only sequence chromosomal DNA, but also to identify which regions a protein of interest specifically binds (Chip-seq), analyze a whole transcriptome of a cell population under investigation (RNA-seq), or find out which RNA regions an RNA binding protein resides (CLIC-seq).

While it is inevitable that many PIs will seriously consider the inclusion of deep sequencing in their next grant proposal, it is not necessarily easy to take the first step and get their feet wet, so to speak. Knowing what format (e.g. 454 for longer reads, HighSeq for higher accuracy, or Ion Torren for bench top convenience) to use and how much to pay requires a vast amount of knowledge and experience. Even when you are done with sample prep, amplification and sequencing, to handle such massive amount of data is not trivial—transporting data alone can be a headache. A database server for storage and analysis requires another layer of expertise. There is no easy solution but to get started somehow. However, be prepared to deal with these issues.

Whether the cost on a type of next generation service is justifiable depends on whether it is required for your purposes. For example, when analyzing a person’s propensity of developing a disease by using known, disease-relevant genetic information, often times exome sequencing is sufficient. This costs anywhere between $1,000 to $3,000 with 100X coverage, significantly less than sequencing a complete genome which typically costs ~$5,000 at ~20x coverage.

High coverage sequencing of maternal blood DNA has been developed into clinically approved prenatal diagnosis of trisomy in Down’s syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities. Transcriptome analysis helped the understanding of how reprogramming works when iPSCs are. Looking forward, with more routine use of deep sequencing we can predict with much more certainty the “off-target” effects of RNAi or cellular toxicity of chromosomal modifications enabled by ZFN, TALEN, or CRISPR. As a matter of fact, we believe that transcriptome sequencing should be required after each RNAi event to prove a specific linkage between knockdown and functions; similarly, whole genome sequencing results need to be provided after making a site directed chromosomal change in the future for high level publications.

*This blog partially resulted from discussions between Jiwu Wang and his colleagues, who are NGS experts at UCSD’s Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Moore Cancer Center, and BGI Americas.

Solving the Big Problems of the World

Science, by nature, is something you do without knowing for sure that it will work. By doing an experiment, testing a theory, or tabulating large data sets to find statistical significance, researchers make small discoveries or incremental improvements on technologies. It is easy for any researcher to get buried under the enormous amount of experimental details while trying to complete a project that lasts for months and years. For a team or an organization, however, it is critical to create a level of alertness of the big questions we try to answer – why are we doing this line of research? Is the technology or theory being developed going to be disruptive in terms of changing the ways of thinking in its field or solving a big challenge that faces the world?

The world does not lack for challenges: there may not be any ice left at the North Pole as early as 2015, there are still a billion people who need reliable electric energy while the carbon fuels may run out on all of us in just a few decades, during which time usable land may not be able to provide enough food for the growing population, cancer or dementia will strike almost everybody if we all live long enough. Well, we have sent humans to the moon; we have completely eradicated smallpox and almost done with polio, can technologies once again enable us to do big things if we all aim high and pull together?

The success stories of future technology companies should not be only the types of Facebook or Twitter, which are nice stories on their own values, but success stories should also include those that deal with big, material, and imminent challenges, provide tools that help people in desperate need. Examples in our biomedical field could include diagnostic kits based on genomic information that will one day be put into each household, so that everybody will be able to decide and receive the most suitable treatment when having an ailment. New businesses will merge because of the technology advancements of deep sequencing, information storage and analysis, biosensors, and stem cell-derived assays and delivery vehicles.

Technologies will continue to develop at a faster pace than most people’s imagination as long as there is a culture that encourages it and a system that allows those with the extraordinary ambition and brains to take their risks. As an example in one of our specific fields, the barriers to making induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have been dramatically lowered through several generations of method revolution only 6 years after the Nobel Prize-winning discovery was first published in 2006 because researchers believe that there will be new opportunities if reprogramming can be done more efficiently and “cleanly”. We have contributed our share of innovation in 2012 and our ambition is to provide everybody with his or her own pluripotent stem cells ready for medical use and to find a solution to most diseases with each individual’s own tissue-derived cells, in another term, point-of-care autologous treatment. It’s unproven, it’s futuristic, but it’s exciting and feasible and we will put every effort to make it happen. Theodore Roosevelt once said that “Far and away the best prize that life has to offer is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.” We are the lucky few.

Companies in Stem Cell Therapies

Geron, spinal cord injury

ViaCyte, diabetes, US$10.1 million from CIRM

Blubird Bio, beta-thalassemia, US$9.3 million from CIRM

StemCells, Alzheimer’s US$20 million from CIRM; spinal cord injury US$20 million from CIRM, stocks rise 148% this year.

Osiris, graft-vs.-host disease (GvHD) in children, approved by Canadian regulator Health Canada

Pluristem Therapeutics, aplastic bone marrow, IPO $30 million, shares up 44%.

Cardio3 BioSciences therapy, heart failure, Phase III in Belgium permitted.

TiGenix, cartilage repair in the knee, commercial production; autoimmune, Crohn’s disease Phase III; quarterly revenue up 152% as reported in Oct, 2012.

Advanced Cell Technology, degenerative eye condition, advancing clinical trials in the US and EU.

New Products to be released at next month’s ASCB annual conference in San Francisco: human mRNA-iPS cells, iPSCs with fluorescent markers, neural pregenitors derived from mRNA-iPSCs.

Categories

- Allele Mail Bag

- cGMP

- Customer Feedback

- Fluorescent proteins

- iPSCs and other stem cells

- nAb: Camelid Antibodies, Nanobodies, VHH

- Next Generation Sequencing (NextGen Seq)

- NIH Budget and You

- oligos and cloning

- Open Forum

- RNAi patent landscape

- SBIR and Business issues

- State of Research

- Synthetic biology

- Uncategorized

- Viruses and cells

- You have the power

Archives

- October 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- January 2018

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- February 2016

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- June 2015

- March 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008